How "The Boys In The Boat" Beat Hitler's Germany - An Interview With Daniel James Brown

|

| Daniel James Brown |

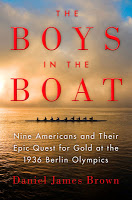

Now, 77 years later, those oarsmen are finally getting their story told in a new book, The Boys in the Boat, by Daniel James Brown.

I ran across this book doing some research on Olympic sports science and was instantly sucked into its underdog beats the villain plot. Brown has captured not only the historical set-up but the human battle and immense odds faced by the crew. Recently, I sat down with the author to find out more about these forgotten heroes.

Daniel, where did you first hear about the story of the 1936 US rowing team? Were you surprised that a book had not been written about their journey?

Daniel James Brown - The story literally walked into the living room, in the form of Judy Willman, my neighbor. She told me that she was reading one of my previous books to her dad, who was in hospice care, living out the last few weeks of his life at her house. He'd liked the earlier book and she wondered if I would come down to meet him. I went down to Judy's house a few days later and met her father, who turned out to be Joe Rantz, the number seven man in the 1936 US Olympic eight-oar crew.

As Joe began to tell me about that I was absolutely mesmerized by the tale. It wasn't just that he and his crew mates had beaten a German boat to win gold in front of Hitler. It was the whole scope of the story--the long hard saga these working class kids from the American West had undertaken to become, arguably, the greatest collegiate crew of all time. It involved enormous physical and psychological stress, moments of devastating set back, moments of great triumph. And it was all set against the backdrop of the Great Depression. Joe's personal story--his loss of his mother, his ill treatment at the hands of his stepmother, his abandonment by his family, his struggles to simply survive gave the story an added dimension of drama and heart. By the time that first conversation was over I knew I had stumbled across the kind of story all writers dream of finding.

Looking back at the 1936 Olympics, everyone knows the story of Jesse Owens vs. Hitler's men but few have heard the story of the men's eights crew. Why do you think that is?

DJB - The larger story has long been known to quite a few Seattlelites, at least those of a certain age. But that's not true nationally. For the most part I think the very existence of this crew and the remarkable sequence of events that led them to Berlin and the gold medal are still going to be news to most Americans. I think that's partly because the Jesse Owens story so dominated the popular imagination in the summer of 1936 that some of the other remarkable things that happened in Berlin--including the remarkable eight-oar crew race--went largely unreported, at least nationally.

Also, I think as Americans we tend to like to celebrate individual achievements, and certainly Jesse's Olympics fit the bill in that regard. They rightly have become part of the American mythos--they help define who we are and what we value--equality, fair play, equal opportunity. I actually think the story of the 1936 Olympic eight [man rowing team] does a similar thing, though it approaches the question from a different angle.

No sport demands such an extreme degree of cooperation as crew. Every detail of every stroke has to be synchronized across eight oars, and it has to happen over and over again in rapid succession. Championship crews have to become one, single entity. Each individual oarsman or oarswoman has to subsume his or her individual ego to the common effort. And in that sense, I think the story of the 1936 crew illustrates what Americans can do when they join in a common effort, when they literally climb in a boat and pull together. Like the Jesse Owens story, it helps define who we are when we are at our best.

No sport demands such an extreme degree of cooperation as crew. Every detail of every stroke has to be synchronized across eight oars, and it has to happen over and over again in rapid succession. Championship crews have to become one, single entity. Each individual oarsman or oarswoman has to subsume his or her individual ego to the common effort. And in that sense, I think the story of the 1936 crew illustrates what Americans can do when they join in a common effort, when they literally climb in a boat and pull together. Like the Jesse Owens story, it helps define who we are when we are at our best.

Today's Olympics world is dominated by sports science, full-time athletes and major government/private funding. Would Joe Rantz, the hero of the gold medal crew, be able to realize his dream today?

DJB - Boy, that's a tough one. I suspect he might not. Like all the other boys in the boat he was just a working class kid. A local farm boy, basically. When he wasn't rowing he was having to make his way in the world, cutting hay, digging ditches, and literally foraging in the woods for food at times. He wouldn't have had time to work out on erg machines, nor the nutrition to build up the kind of massive body strength of today's oarsmen. (Male oarsmen of his day and age tended to be skinny beanpoles, maybe 175 pounds and 6'2". Today the average is probably closer to 200 pounds).

He wouldn't have known what his VO2 max was. He didn't face competition from recruits from all over the world, nor even other American kids on full ride scholarships. There was no such thing as a rowing scholarship at Washington in 1933. But for character, for sheer guts and drive, I think he--and all the other boys in that boat--would have stood out as exceptional today.

Our blog is about the cognitive side of sports; how your brain enables you to compete. Are the mental aspects of rowing purely motivational or are there cognitive skills and strategies necessary to win?

DJB - There's a huge motivational component. It's a downright brutal sport, so you certainly have to be enormously tough mentally to undertake it on the level of an Olympic contender. But yes, there is also a huge array of cognitive skills that have to be mastered. The sport isn't one of simple brawn by any means; it has much more to do with fine tuning every movement you make to get the maximum amount of drive out of a given expenditure of energy. That means constant attention to very small details of technique, and the mental acuity to keep all those details in mind as you repeat the stroke at varying levels of intensity over and over again.

There is also the matter of meshing mentally with the other seven people wielding oars. That in itself requires a good deal of mental dexterity. I think one of the most interesting parts of the sport, though, is the kind of mental chess game that goes on among coxswains in a race. There is only so much muscle power, energy, and stamina in even the best boats. The coxswain always has the problem of how and more importantly when to use turn all that power loose. Do it too early and his crew will burn out before the finish line; do it too late and they will never catch up in time. So coxswains keep wary eyes on one another throughout a race trying to guess when the others are going to make their move. Getting that right, along with knowing your crew and knowing the capabilities of the crews in the other boats are absolutely key to winning crew races.

Every ounce of weight in a boat has to be justified by it's output, and a lot of coaches think the three pounds or so of gray matter in their coxswains' heads are the most important pounds in the boat.

Finally, what can you tell us about the upcoming movie adaptation directed by Kenneth Branagh?

Thank you Daniel for your time and a great book!