HGH - Human Growth Hoax?

/

Athletes, both professional and amateur, as well as the general public are convinced that human growth hormone (HGH), Erythropoietin (EPO) and anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) are all artificial and controversial paths to improved performance in sports. The recent headlines that have included Barry Bonds, Marion Jones, Floyd Landis, Dwayne Chambers, Jose Canseco, Jason Giambi, Roger Clemens and many lesser known names (see the amazingly long list of doping cases in sport) have referred to these three substances interchangeably leaving the public confused about who took what from whom. With so many athletes willing to gamble with their futures, they must be confident that they will see significant short-term results.

So, is it worth the risk? Two very interesting recent studies provide some answers on at least one of the substances, HGH.

A team at the Stanford University School of Medicine, led by Hau Liu MD, recently reviewed 27 historical studies on the effects of HGH on athletic performance, dating back to 1966 (see reference below). They wanted to see if there were any definitive links between HGH use and improved results. In some of the studies, test volunteers who received HGH did develop more lean body mass, but also developed more lactate during aerobic testing which inhibited rather than helped performance. While their muscle mass increased, other markers of athletic fitness, such as VO2max remained unchanged. “The key takeaway is that we don’t have any good scientific evidence that growth hormone improves athletic performance,” said senior author Andrew Hoffman, MD, professor of endocrinology, gerontology and metabolism.

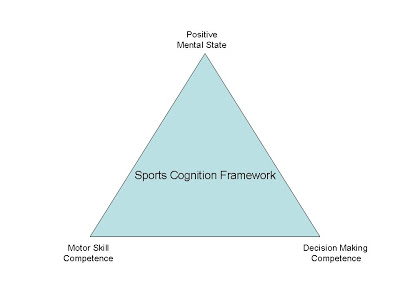

Both Liu and Hoffman cautioned that the amounts of HGH given to these test subjects may be much lower than the the purported levels claimed to be taken by professional athletes. They also pointed out that at a professional level, a very slight improvement might be all that is necessary to get an edge of your opponent. Hoffman also added an insightful comment, “So much of athletic performance at the professional level is psychological.” If an athlete takes HGH, sees some muscle mass growth and isn't 100% sure of its performance capabilities, might he assume he now has other "Superman" powers?

That is exactly the premise that a research team from Garvan Institute of Medical Research in Sydney, Australia used to find out if HGH users simply relied on a placebo effect. Sixty-four participants, young adult recreational athletes, were divided into two groups of 32 and tested for a baseline of athletic ability in endurance, strength, power and sprinting. One group received growth hormone and the other group received a simple placebo. It was a "double-blind" study in that neither the participants nor the researchers knew during the testing which substance each group received.

At the end of the 8 week treatment, the athletes were asked if they thought they were in the HGH group or the placebo group. Half of the group that had received the placebo incorrectly guessed that they were on HGH. Not too surprisingly, the majority of the "incorrect guessers" were men. Here's where it gets interesting. The incorrect guessers also thought that their athletic abilities had improved over the 8 week period. The team retested all of the placebo group and actually did find improvement across all of the tests, but only significantly in the high-jump test.

Jennifer Hansen, a nurse researcher and Dr. Ken Ho, head of the pituitary research unit at Garvan have not released the data on the group that did receive the HGH, but they will in their final report coming soon.

So, let's recap. On the one hand, we have a research review that claims there is not yet any scientific evidence that HGH actually improves sports performance. Yet, we have hundreds, if not thousands, of athletes illegally using HGH for performance gain. Showing the effect of the "if its good enough for them, its good enough for me" beliefs of the public regarding professional athlete use of HGH, we now have research that shows even those who received a placebo, but believed they were taking HGH not only thought they were improving but actually did improve a little. Once again, we see the power of our own natural, non-supplemented brain to convince (or fool) ourselves to perform at higher levels than we thought possible.

Liu, H., Bravata, D.M., Olkin, I., Friedlander, A., Liu, V., Roberts, B., Bendavid, E., Saynina, O., Salpeter, S.R., Garber, A.M. (2008). Systematic review: the effects of growth hormone on athletic performance.. Annals of Internal Medicine, 148(10), 747-758.

So, is it worth the risk? Two very interesting recent studies provide some answers on at least one of the substances, HGH.

A team at the Stanford University School of Medicine, led by Hau Liu MD, recently reviewed 27 historical studies on the effects of HGH on athletic performance, dating back to 1966 (see reference below). They wanted to see if there were any definitive links between HGH use and improved results. In some of the studies, test volunteers who received HGH did develop more lean body mass, but also developed more lactate during aerobic testing which inhibited rather than helped performance. While their muscle mass increased, other markers of athletic fitness, such as VO2max remained unchanged. “The key takeaway is that we don’t have any good scientific evidence that growth hormone improves athletic performance,” said senior author Andrew Hoffman, MD, professor of endocrinology, gerontology and metabolism.

Both Liu and Hoffman cautioned that the amounts of HGH given to these test subjects may be much lower than the the purported levels claimed to be taken by professional athletes. They also pointed out that at a professional level, a very slight improvement might be all that is necessary to get an edge of your opponent. Hoffman also added an insightful comment, “So much of athletic performance at the professional level is psychological.” If an athlete takes HGH, sees some muscle mass growth and isn't 100% sure of its performance capabilities, might he assume he now has other "Superman" powers?

That is exactly the premise that a research team from Garvan Institute of Medical Research in Sydney, Australia used to find out if HGH users simply relied on a placebo effect. Sixty-four participants, young adult recreational athletes, were divided into two groups of 32 and tested for a baseline of athletic ability in endurance, strength, power and sprinting. One group received growth hormone and the other group received a simple placebo. It was a "double-blind" study in that neither the participants nor the researchers knew during the testing which substance each group received.

At the end of the 8 week treatment, the athletes were asked if they thought they were in the HGH group or the placebo group. Half of the group that had received the placebo incorrectly guessed that they were on HGH. Not too surprisingly, the majority of the "incorrect guessers" were men. Here's where it gets interesting. The incorrect guessers also thought that their athletic abilities had improved over the 8 week period. The team retested all of the placebo group and actually did find improvement across all of the tests, but only significantly in the high-jump test.

Jennifer Hansen, a nurse researcher and Dr. Ken Ho, head of the pituitary research unit at Garvan have not released the data on the group that did receive the HGH, but they will in their final report coming soon.

So, let's recap. On the one hand, we have a research review that claims there is not yet any scientific evidence that HGH actually improves sports performance. Yet, we have hundreds, if not thousands, of athletes illegally using HGH for performance gain. Showing the effect of the "if its good enough for them, its good enough for me" beliefs of the public regarding professional athlete use of HGH, we now have research that shows even those who received a placebo, but believed they were taking HGH not only thought they were improving but actually did improve a little. Once again, we see the power of our own natural, non-supplemented brain to convince (or fool) ourselves to perform at higher levels than we thought possible.

Liu, H., Bravata, D.M., Olkin, I., Friedlander, A., Liu, V., Roberts, B., Bendavid, E., Saynina, O., Salpeter, S.R., Garber, A.M. (2008). Systematic review: the effects of growth hormone on athletic performance.. Annals of Internal Medicine, 148(10), 747-758.