In January, first-year Kentucky high school football coach David Jason Stinson pleaded not guilty to charges of reckless homicide in the death of Max Gilpin, a 15-year-old offensive lineman. Gilpin collapsed Aug. 20 while running sprints with the team on a day when the heat index reached 94 degrees.

Last week, Stinson pleaded the fifth amendment and did not answer questions in the civil court case against him, while his criminal case is pending. The case could signal a landmark shift in the expectation for how coaches deal with struggling players on a hot day.

Gilpin's body temperature was 107 degrees when he reached the hospital and he died three days later from heat stroke. The risks of heat-related diseases to athletes, both young and old, are always present but the warning signs are often hidden.

Since 1995, 33 football players have died from heat stroke, according to an annual report from the University of North Carolina. Frederick O. Mueller, professor of exercise and sports science at UNC and the author of the report, calls the figure unacceptable.

"There's no excuse for any number of heat stroke deaths, since they are all preventable with the proper precautions," Mueller said.

Wake-up call

The wake-up call has been delivered to all coaches. They must be able to recognize a struggling player and resist the assumption that they're just being lazy. Dave Stengel, the prosecuting attorney in the Stinson case, described the coach's responsibility: "This is not about football. This is not about coaches," he said. "It's about a trained adult who was in charge of the health and welfare of a child."

Heat stroke is the most serious of the four levels of heat illness. Progressing from dehydration to heat cramps to heat exhaustion without intervention may lead to heat stroke where the core body temperature exceeds 104 degrees.

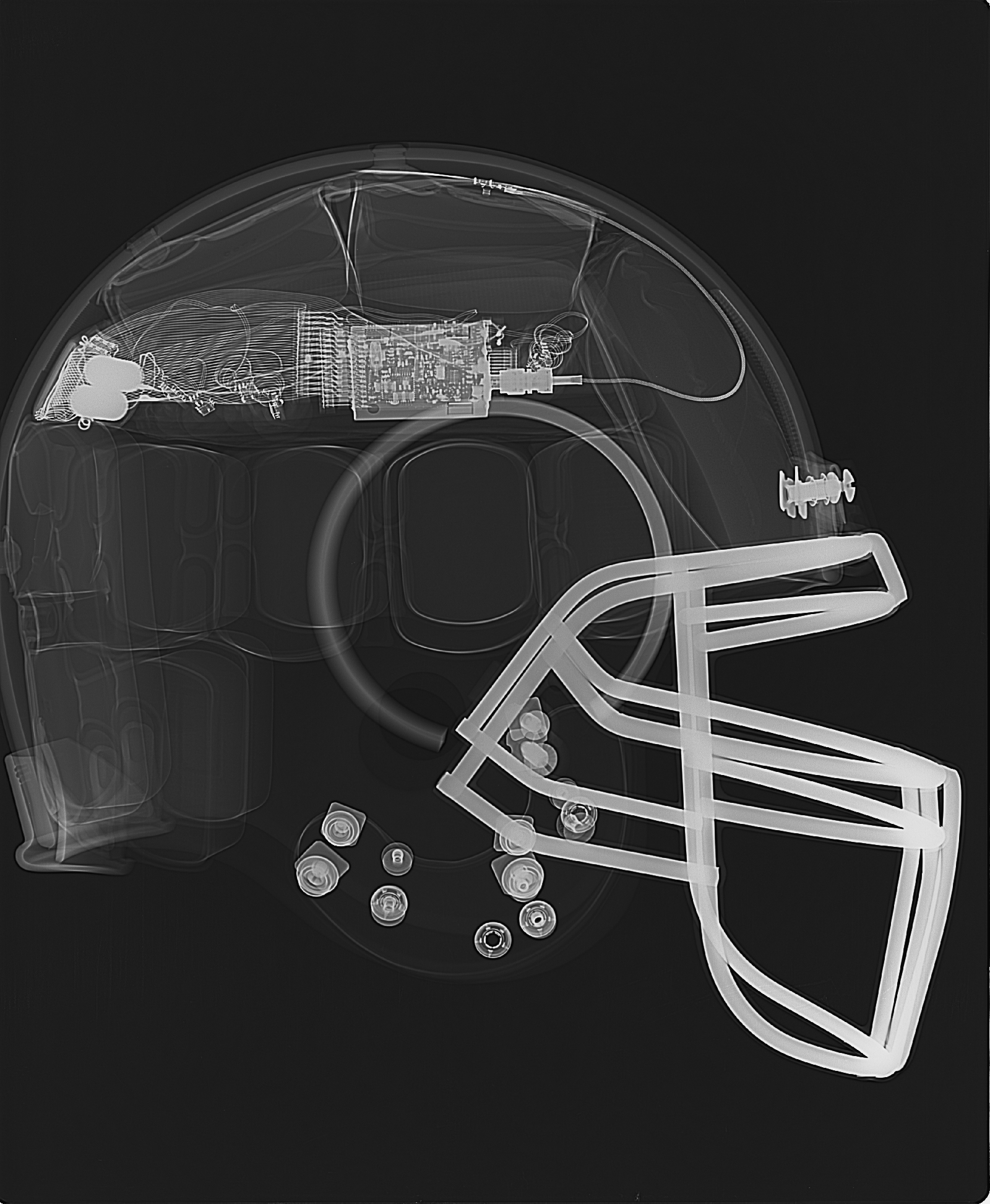

Since the common symptoms (nausea, incoherence, fatigue, weakness, vomiting, muscle cramps) of heat exhaustion and heat stroke are similar, it can be hard to tell when a player has crossed that dangerous line. That is why most medical professionals recommend a proactive approach to playing in the heat. Slow acclimation to the heat over several days, planned and regular water breaks, and reduced activity when the heat index rises will help prevent problems.

The National Athletic Trainers Association has published

guidelines for parents and coaches to follow.

What happens

In a 2008 study, researchers explored the complex interactions in the human body when subjected to high heat and high levels of physical activity. José González-Alonso, Professor of Sport and Exercise Physiology at Brunel University, and his team looked at the competing demands for blood flow that heat and exercise cause and the physiological breakdown that eventually occurs.

Our bodies actually gain heat from both the environment and our own muscle movement. When the air temperature is greater than our skin temperature, heat will be transferred into our body. When we exercise, our contracting muscles also produce heat. In fact, about 75 percent of the energy expended is lost to heat rather than power.

To cool ourselves down, two processes must take place: increased blood flow to the skin, and sweating.

The evaporation of sweat to the air pulls heat away from the body. One kilogram of sweat evaporated from the skin will remove 580 kilocalories of heat from the body. If fluids are not replenished by drinking water, the sweating process slows down and the core body temperature rises.

Effects on body and brain

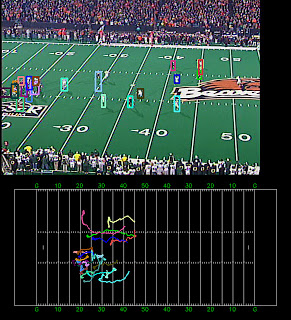

When running sprints on a football field in the heat, a player's heart needs to do double-duty; pumping blood to his muscles and to the skin. González-Alonso found that the heart will serve the metabolic demands of the muscles first, allowing the skin blood flow to diminish, which raises body temperature. The study also found that fatigue is not a result of tired muscles, but rather from an increase in brain temperature.

As a safety valve, the brain sends signals of fatigue that lower our drive to keep going. If forced to continue by an over demanding coach, the downward spiral will continue. If the player does collapse, immediate attention is the key to survival.

"If you cool someone right away, on site, they don't die - period," said Dr. Doug Casa of the University of Connecticut and a national leader in heat-stroke prevention. "The key to surviving heat stroke is getting your temperature (down) to approximately 104 in about 20 minutes."

Please visit my other sports science articles at LiveScience.com