Why Are Great Soccer Players So Rare?

/

An athlete’s level of greatness is often measured by the opinions of his

or her peers while they’re playing and especially when they retire.

Being recognized as one of the best by those who understand what it

takes is rare. This week, one of the world’s greatest soccer players of

the last 30 years retired, yet he could walk down most streets in

America without being recognized.

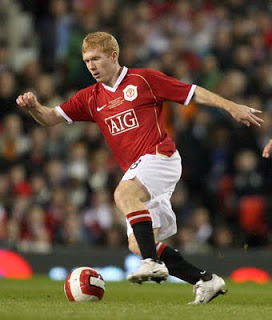

After 17 seasons, Paul Scholes of Manchester United played in his final tribute game last week and will become a coach at the club he’s been part of since his teens.

While not a household name in the U.S. like Messi or Ronaldo or Beckham, he has earned the respect of the greatest players of his time.

“My toughest opponent? Scholes of Manchester,” said Zinedine Zidane, French World Cup Winner and 3-time world player of the year. “He is the complete midfielder. He’s almost untouchable in what he does.You rarely come across the complete player, but Scholes is as close to it as you can get.”

“In the last 15 to 20 years the best central midfielder that I have seen — the most complete — is Scholes,” said Xavi Hernandez, Barcelona midfield maestro, arguably the best midfielder in the world at the moment. “Scholes is a spectacular player who has everything. He can play the final pass, he can score, he is strong, he never gets knocked off the ball and he doesn’t give possession away.”

“He’s always one of those people others talk about,” said David Beckham, world soccer icon and a former teammate. “Even when playing at Real Madrid, the players always said to me ‘what’s he like’? They respect him as a footballer and see him as the ultimate.”

So, what makes him different? What is the secret ingredient that makes a few soccer players better than the thousands that come and go? Obviously, many clubs would pay huge sums of money to find out. Recently, two teams of researchers from the University of Queensland tried to narrow down the options.

In 2009, the university’s semi-professional soccer team was tested for their general athletic abilities across sixteen different tasks to get a measure of their inherent talents (speed, agility, strength, etc.) Then they were paired off in games of “soccer tennis” which is what it sounds like - two players on a tennis court with a soccer ball kicking and heading it back and forth across the net.

Dr. Robbie Wilson and his team wanted to see if differences in basic athletic abilities were correlated with being a more skilled soccer player. "There was no evidence of any correlations between maximal athletic performance and skill", concludes Dr. Wilson. "Our studies suggest that skill is just as important, if not more important, than athletic ability in determining performance of complex traits, such as performance on the football field".

Alright, so skill is at least as important as raw physical gifts. Is skill enough? There are plenty of skilled players who don’t become Paul Scholes. This year, Dr. Gwendolyn David, also at the University of Queensland, picked up the trail from her mentor, Dr. Wilson. Her team first tested 27 semi-pro players in individual soccer skills like dribbling speed, volley accuracy, and passing accuracy.

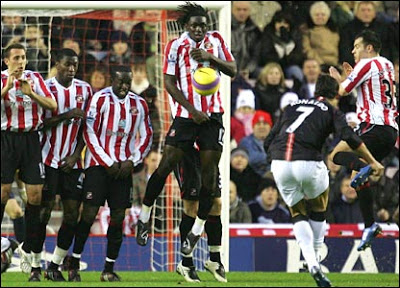

Next they observed these players in actual game situations watching for the “complex tasks” that combine the individual skills into a complete performance. These included ball-interception, challenging another player for the ball, passing, shooting and blocking the ball.

Judging from the results, it was clear to Dr. David that superior skills do not translate to better game play. "Athletic skill abilities measured in the lab were not associated with any measure of performance on the pitch. In other words, it's not your ability, it's what you do with it that counts,” writes Dr. David. She recommends that youth coaches spend more time in actual game conditions rather than just focusing on individual skill development.

Despite these results, we’re still left searching for the secret of Scholes. It seems to be more than physical abilities and soccer skills. Others have commented on his uncanny sense of his surroundings. His one and only manager, Sir Alex Ferguson, may sum it up best, "He has an awareness of what’s happening around him on the edge of the box which is better than most players. As a kid he always had a knack of arriving in the right area just at the right time, but he’s proving just as effective from outside the box because he’s using his experience in the right way. One of the greatest football brains Manchester United has ever had."

Join me on Twitter at Dan Peterson and Axon Potential

See also: Artificial Intelligence Tackles Football Knowledge

and Kicking Style Of Women Soccer Players May Cause Injury

After 17 seasons, Paul Scholes of Manchester United played in his final tribute game last week and will become a coach at the club he’s been part of since his teens.

While not a household name in the U.S. like Messi or Ronaldo or Beckham, he has earned the respect of the greatest players of his time.

“My toughest opponent? Scholes of Manchester,” said Zinedine Zidane, French World Cup Winner and 3-time world player of the year. “He is the complete midfielder. He’s almost untouchable in what he does.You rarely come across the complete player, but Scholes is as close to it as you can get.”

“In the last 15 to 20 years the best central midfielder that I have seen — the most complete — is Scholes,” said Xavi Hernandez, Barcelona midfield maestro, arguably the best midfielder in the world at the moment. “Scholes is a spectacular player who has everything. He can play the final pass, he can score, he is strong, he never gets knocked off the ball and he doesn’t give possession away.”

“He’s always one of those people others talk about,” said David Beckham, world soccer icon and a former teammate. “Even when playing at Real Madrid, the players always said to me ‘what’s he like’? They respect him as a footballer and see him as the ultimate.”

So, what makes him different? What is the secret ingredient that makes a few soccer players better than the thousands that come and go? Obviously, many clubs would pay huge sums of money to find out. Recently, two teams of researchers from the University of Queensland tried to narrow down the options.

In 2009, the university’s semi-professional soccer team was tested for their general athletic abilities across sixteen different tasks to get a measure of their inherent talents (speed, agility, strength, etc.) Then they were paired off in games of “soccer tennis” which is what it sounds like - two players on a tennis court with a soccer ball kicking and heading it back and forth across the net.

Dr. Robbie Wilson and his team wanted to see if differences in basic athletic abilities were correlated with being a more skilled soccer player. "There was no evidence of any correlations between maximal athletic performance and skill", concludes Dr. Wilson. "Our studies suggest that skill is just as important, if not more important, than athletic ability in determining performance of complex traits, such as performance on the football field".

Alright, so skill is at least as important as raw physical gifts. Is skill enough? There are plenty of skilled players who don’t become Paul Scholes. This year, Dr. Gwendolyn David, also at the University of Queensland, picked up the trail from her mentor, Dr. Wilson. Her team first tested 27 semi-pro players in individual soccer skills like dribbling speed, volley accuracy, and passing accuracy.

Next they observed these players in actual game situations watching for the “complex tasks” that combine the individual skills into a complete performance. These included ball-interception, challenging another player for the ball, passing, shooting and blocking the ball.

Judging from the results, it was clear to Dr. David that superior skills do not translate to better game play. "Athletic skill abilities measured in the lab were not associated with any measure of performance on the pitch. In other words, it's not your ability, it's what you do with it that counts,” writes Dr. David. She recommends that youth coaches spend more time in actual game conditions rather than just focusing on individual skill development.

Despite these results, we’re still left searching for the secret of Scholes. It seems to be more than physical abilities and soccer skills. Others have commented on his uncanny sense of his surroundings. His one and only manager, Sir Alex Ferguson, may sum it up best, "He has an awareness of what’s happening around him on the edge of the box which is better than most players. As a kid he always had a knack of arriving in the right area just at the right time, but he’s proving just as effective from outside the box because he’s using his experience in the right way. One of the greatest football brains Manchester United has ever had."

Join me on Twitter at Dan Peterson and Axon Potential

See also: Artificial Intelligence Tackles Football Knowledge

and Kicking Style Of Women Soccer Players May Cause Injury