Better Golf Ball Design Helps You Play Better Golf

/When it comes to improving your golf game, you can spend thousands of dollars buying the latest titanium-induced, Tiger-promoted golf clubs; taking private lessons from the local "I used to be on the Tour" pro; or trying every slice-correcting, swing-speed-estimating, GPS-distance-guessing gadget. But, in the end, it’s about getting that little white sphere to go where you intended it to go. Don't worry, there are many very smart people trying to help you by designing the ultimate golf ball. Of course, they are also after a slice of this billion dollar industry, as any technological advancement that can grab a few more market share points is worth the investment.

In fact, the golf ball wars can get nasty. Earlier this month, Callaway Golf won a court order permanently halting sales of the industry's leading ball, Titleist's Pro V1, arguing patent infringements involving its solid core technology which Callaway acquired when it bought Spaulding/Top Flite in 2003. Titleist disagrees with the decision and will appeal, but in the meantime has altered its manufacturing process so that the patents in question are not used.

The challenge for golf ball manufacturers is to design a better performing ball within the constraints set by United States Golf Association. The USGA enforces limits on the size, weight and initial performance characteristics in an attempt to keep the playing field somewhat level. Every "sanctioned" golf ball must weigh less than 1.62 ounces with a diameter smaller than 1.68 inches. It also must have a similar initial velocity when hit with a metal striker, and rebound at the same angle and speed when hit against a metal block. So, what is left to tinker with? Manufacturers have focused on the internal materials in the ball and its cover design.

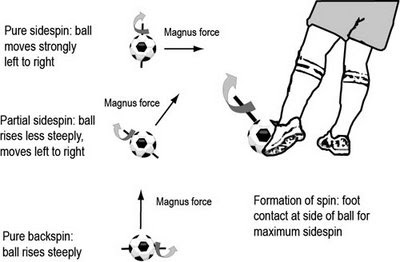

Today's balls have 2, 3 or 4 layers of different internal polymer materials to be able to respond differently when hit with a driver versus, say, a wedge. When hit with a driver at much higher swing speed, the energy transfer goes all the way to the core by compressing ball, reducing backspin. During a slower swing with a club that has more angle loft, the energy stays closer to the surface of the ball and allows the grooves of the club to grab onto the ball's cover producing more spin. When driving the ball off of the tee, the preference is more distance and less loft, so a lower backspin is required. For closer shots, more backspin and control are needed.

The Science of Dimples

Think about a boat moving through water. At the front of the boat, the water moves smoothly around the sides of the boat, but eventually separates from the boat on the back side. This leaves behind a turbulent wake where the water is agitated and creates a lower pressure area. The larger the wake, the more drag is created. A ball in flight has the same properties.

The secret then is how to reduce this wake behind the ball. Enter the infamous golf ball dimples. Dimples on a golf ball create a thin turbulent boundary layer of air molecules that sticks to the ball's contour longer than on a smooth ball. This allows the flowing air to follow the ball's surface farther around the back of the ball, which decreases the size of the wake. In fact, research has shown that a dimpled ball travels about twice as far as a smooth ball.

So, the design competition comes down to perfecting the dimple, since not all dimples are created equal! The number, size and shape can have a dramatic impact on performance. Typically, today's balls have 300-500 spherically shaped dimples, each with a depth of about .010 inch. However, varying just the depth by .001 inch can have dramatic effects on the ball's flight.

Regarding shape, these traditional round dimple patterns cover up to 86 percent of the surface of the golf ball. To create better coverage, Callaway Golf's HX ball uses hexagon shaped dimples that can create a denser lattice of dimples leaving fewer flat spots. Creating just the right design has traditionally been a trial-and-error process of creating a prototype then testing in a wind tunnel. This time-consuming process does not allow for the extreme fine-tuning of the variables.

Simulation Solution

At the 61st Meeting of the American Physical Society's Division of Fluid Dynamics this week in San Antonio, a team of researchers from Arizona State University and the University of Maryland is reporting new findings that may soon give golf ball manufacturers a more efficient method of testing their designs. Their research takes a different approach, using mathematical equations that model the physics of a golf ball in flight. ASU's Clinton Smith, a Ph.D. student and his advisor Kyle Squires collaborated with Nikolaos Beratlis and Elias Balaras at the University of Maryland and Masaya Tsunoda of Sumitomo Rubber Industries, Ltd. The team has been developing highly efficient algorithms and software to solve these equations on parallel supercomputers, which can reduce the simulation time from years to hours.

Now that the model and process is in place, the next step is to begin the quest for the ultimate dimple. In the meantime, when someone asks you, "What's your handicap?" you can confidently tell them, "Well, my golf ball's design does not optimize its drag coefficient which results in a lower loft and spin rate from its poor aerodynamics."

Please visit my other articles on Livescience.com

Related Articles on Sports Are 80 Percent Mental:

Putt With Your Brain - Part 2

Please visit my other articles on Livescience.com

Related Articles on Sports Are 80 Percent Mental:

Putt With Your Brain - Part 2