NFL Linemen Trade Health For Super Bowl Rings

/

When the Arizona Cardinals met the Pittsburgh Steelers in Super Bowl XLIII, every starting offensive lineman was a member of the 300-pound club.

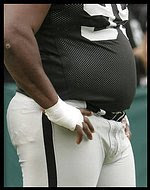

This season, there were more than 600 players — about 20 percent of the league — in triple donuts. Even with 6-foot plus heights, their Body Mass Index (BMI) levels are all in the range of grade 2 obesity, one step below what's called morbid obesity.

This super-sizing of NFL players has accelerated in recent years, and some studies suggest health risks are growing. But studies are conflicting on this point.

And the big question on the minds of coaches and owners: Do heavier players mean more wins? No, says one NFL executive.

Strong vs. fat

The trend towards the ever-expanding football player, especially on the offensive and defensive lines, has accelerated over the last 20 years. From 1920-1984 no more than eight players in the league were over 300 pounds.

The motivation to be bigger comes from the perceived advantages on the field. When Nick Saban, now head coach at Alabama, was drafting players for the Miami Dolphins, he said: "I always say it this way: They have weight classes in boxing for a reason. The heavyweights don't fight the lightweights. What's the reason for that? Because if a big guy is just as good as a little guy, the little guy doesn't have much of a chance."

BMI is a measure of obesity based on a height to weight ratio. Often the apparently risky BMI of large athletes is dismissed because of the percentage of muscle included in their mass. The question becomes whether "big and strong" is any less dangerous than "big and fat."

Last year, Mayo Clinic researchers studied the cardiovascular health of 233 retired NFL players, aged 35-65. They found that in players less than 50 years old, 82 percent had either plaque or carotid narrowing of their arteries greater than the 75th percentile of the population, adjusted for age, sex and race. This condition could lead to a restriction of blood flow causing a heart attack or stroke.

Conflicting results emerged from a University of Texas study later in the year. They compared the health of 201 former NFL players and compared them with the population-based Dallas Heart Study and the Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study. Compared to the control group of men, retired players had a significantly lower prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, sedentary lifestyles and metabolic syndrome.

"Despite their large body size, retired NFL players do not have a greater prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors nor CAC than community controls," Alice Y. Chang, lead author and assistant professor of Internal Medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School in Dallas. "Age and high cholesterol levels, not body size, were the most significant predictors of sub-clinical coronary atherosclerosis among retired NFL players."

Does it matter?

Does it matter?

Jackie Buell, director of sports nutrition at Ohio State University, recently released a study focused specifically on players with metabolic syndrome. This condition is characterized by a group of symptoms that include excess fat in the abdominal area, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes and elevated levels of triglyceride. Having one or more of these symptoms increases the risk of future heart disease or attacks.

Buell's study measured these factors in 70 current college football linemen. Thirty-four players had at least three risk factors, while eight had four and one had all five risk factors.

"We understand these athletes want to be big, but they can't assume all their weight gain is lean mass just because they're lifting weights and taking protein supplements," Buell said. "The bottom line is we're seeing more and more abdominal obesity. And these findings show that athletes aren't necessarily off the hook when it comes to health risks."

Are the potential health problems worth the risk of garnering a Super Bowl ring?

Indianapolis Colts president Bill Polian recently asked that very question to help his NFL draft planning. He compared the winning percentages with the average weight of NFL teams over a recent ten year period. "We found higher weight had no bearing on winning — none," Polian said. "There was a lot of noise about 'big is the answer.' We tested it. It's not valid."

Please visit my other articles on Livescience.com

This season, there were more than 600 players — about 20 percent of the league — in triple donuts. Even with 6-foot plus heights, their Body Mass Index (BMI) levels are all in the range of grade 2 obesity, one step below what's called morbid obesity.

This super-sizing of NFL players has accelerated in recent years, and some studies suggest health risks are growing. But studies are conflicting on this point.

And the big question on the minds of coaches and owners: Do heavier players mean more wins? No, says one NFL executive.

Strong vs. fat

The trend towards the ever-expanding football player, especially on the offensive and defensive lines, has accelerated over the last 20 years. From 1920-1984 no more than eight players in the league were over 300 pounds.

The motivation to be bigger comes from the perceived advantages on the field. When Nick Saban, now head coach at Alabama, was drafting players for the Miami Dolphins, he said: "I always say it this way: They have weight classes in boxing for a reason. The heavyweights don't fight the lightweights. What's the reason for that? Because if a big guy is just as good as a little guy, the little guy doesn't have much of a chance."

BMI is a measure of obesity based on a height to weight ratio. Often the apparently risky BMI of large athletes is dismissed because of the percentage of muscle included in their mass. The question becomes whether "big and strong" is any less dangerous than "big and fat."

Last year, Mayo Clinic researchers studied the cardiovascular health of 233 retired NFL players, aged 35-65. They found that in players less than 50 years old, 82 percent had either plaque or carotid narrowing of their arteries greater than the 75th percentile of the population, adjusted for age, sex and race. This condition could lead to a restriction of blood flow causing a heart attack or stroke.

Conflicting results emerged from a University of Texas study later in the year. They compared the health of 201 former NFL players and compared them with the population-based Dallas Heart Study and the Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study. Compared to the control group of men, retired players had a significantly lower prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, sedentary lifestyles and metabolic syndrome.

"Despite their large body size, retired NFL players do not have a greater prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors nor CAC than community controls," Alice Y. Chang, lead author and assistant professor of Internal Medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School in Dallas. "Age and high cholesterol levels, not body size, were the most significant predictors of sub-clinical coronary atherosclerosis among retired NFL players."

Jackie Buell, director of sports nutrition at Ohio State University, recently released a study focused specifically on players with metabolic syndrome. This condition is characterized by a group of symptoms that include excess fat in the abdominal area, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes and elevated levels of triglyceride. Having one or more of these symptoms increases the risk of future heart disease or attacks.

Buell's study measured these factors in 70 current college football linemen. Thirty-four players had at least three risk factors, while eight had four and one had all five risk factors.

"We understand these athletes want to be big, but they can't assume all their weight gain is lean mass just because they're lifting weights and taking protein supplements," Buell said. "The bottom line is we're seeing more and more abdominal obesity. And these findings show that athletes aren't necessarily off the hook when it comes to health risks."

Are the potential health problems worth the risk of garnering a Super Bowl ring?

Indianapolis Colts president Bill Polian recently asked that very question to help his NFL draft planning. He compared the winning percentages with the average weight of NFL teams over a recent ten year period. "We found higher weight had no bearing on winning — none," Polian said. "There was a lot of noise about 'big is the answer.' We tested it. It's not valid."

Please visit my other articles on Livescience.com