At a recent baseball game, the 12-year-old second baseman on my son's team had a ground ball take a nasty hop, hitting him just next to his right eye. He was down on the field for several minutes and was later diagnosed at the hospital with a concussion.

Thankfully, acute baseball injuries like this are on the decline, according to a new report. However, several leading physicians say overuse injuries of young players caused by too much baseball show no signs of slowing down.

Our

unlucky infielder's hospital injury report may become part of a national database called the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS), part of the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. It monitors 98 hospitals across the country for reports on all types of injuries.

Bradley Lawson, Dawn Comstock and Gary Smith of Ohio State University filtered this data to find just baseball-related injuries to kids under 18 from 1994-2006.

During that period, they found that more than 1.5 million young players were treated in hospital emergency rooms, with the most common injury being, you guessed it, being hit by the ball, and typically in the face.

The good news is that the annual number of baseball injuries has decreased by 24.9 percent over those 13 years. The researchers credit the decline to the increased use of protective equipment.

"Safety equipment such as age-appropriate breakaway bases, helmets with properly-fitted face shields, mouth guards and reduced-impact safety baseballs have all been shown to reduce injuries," Smith said. "As more youth leagues, coaches and parents ensure the use of these types of safety equipment in both practices and games, the number of baseball-related injuries should continue to decrease. Mouth guards, in particular, should be more widely used in youth baseball."

Their research is detailed in the latest edition of the journal

Pediatrics.

The bad news is ...

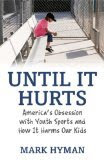

While accident-related injuries are down, preventable injuries from overuse still seem to be a problem, according to author Mark Hyman. In his recent book, "

Until It Hurts," Hyman admits his own mistakes in pressuring his 14-year-old son to continue pitching with a sore arm, causing further injury.

Surprised by his own unwillingness to listen to reason, Hyman, a long-time journalist, researched the growing trend of high-pressure parents pushing their young athletes too far, too fast.

"Many of the physicians I spoke with told me of a spike in overuse injuries they had witnessed," Hyman told

Livescience. "As youth sports become increasingly competitive — climbing a ladder to elite teams, college scholarships, parental prestige and so on — children are engaging in a range of risky behaviors."

One expert he consulted was Dr. Lyle Micheli, founder of one of the country's first pediatric sports medicine clinics at Children's Hospital in Boston. Micheli estimates that 75 percent of the young patients he sees are suffering from some sort of overuse injury, versus 20 percent back in the 1990s.

"As a medical society, we've been pretty ineffective dealing with this," Micheli said. "Nothing seems to be working."

Young surgeries

In severe overuse cases for

baseball pitchers, the end result may be ulnar collateral ligament surgery, better known as "Tommy John" surgery. Dr. James Andrews, known for performing this surgery on many professional players, has noticed an alarming trend in his practice. Andrews told

The Oregonian last month that more than one-quarter of his 853 patients in the past six years were at the high school level or younger, including one 7-year-old.

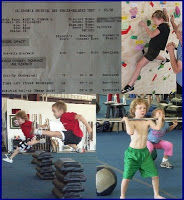

Last spring, Andrews and his colleagues conducted a study comparing 95 high-school pitchers who required surgical repair of either their elbow or shoulder with 45 pitchers that did not suffer injury.

They found that those who pitched for more than eight months per year were 500 percent more likely to be injured, while those who pitched more than 80 pitches per game increased their injury risk by 400 percent. Pitchers who continued pitching despite having arm fatigue were an incredible 3,600 percent more likely to do serious damage to their arm.

Hyman encourages parents to keep youth sports in perspective. "I think that, generally, parents view sports as a healthy and wholesome activity. That's a positive. But, we live in hyper-competitive culture, and parents like to see their kids competing," he said. "It's not only sports. It's ballet and violin and SAT scores and a host of other things. It's in our DNA."

Please visit my other sports science articles at Livescience.com.