Why NFL Combine Results For Jadeveon Clowney And Johnny Manziel Don't Matter

/

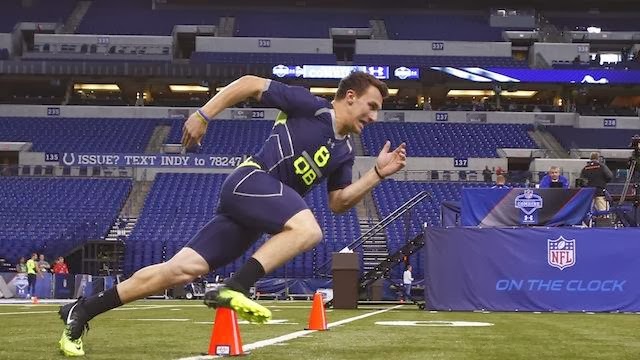

With the Olympics over and the NBA and NHL not yet into playoff mode, the NFL knows its fans need a shot of football in late winter. To prepare us (and the team general managers and coaches) for the NFL Draft in early May, 300 of the best college football players visited Lucas Oil Stadium in Indianapolis last week for the annual NFL Scouting Combine.

While there are specific drills that the players go through for each position, it is the six workout drills, testing strength, agility, jumping and speed, that generate the most TV coverage and conversation. However, sport science researchers keep putting out study after study that shows that not only are the six tests redundant but that they also have little correlation to actual NFL performance, making them poor predictors for success.

First, let’s break down the drills themselves. For the best explanation, watch NFL analyst Mike Mayock explain the process.

40-yard dash - As the marquee event at the Combine, the 40-yard dash, with interval times taken at 10 and 20 yards, tests all-out sprint speed.

3-Cone drill - With 3 cones set-up in an L shape, the player runs a specific pattern around the cones, testing his agility and change of direction speed.

Shuttle run - Testing lateral quickness, players run 5 yards, switch directions, run 10 yards, then run back again for 5 yards.

Vertical jump - Measured as the difference between a player’s reach, standing flat-footed and reaching up, and how high they can jump with no run-up.

Broad jump - A test of horizontal leaping, the player starts with two feet stationary and jumps out as far as possible while still being able to hold his landing without falling.

Bench press - The Combine’s only measure of strength tests the number of bench press repetitions of 225 pounds before exhaustion.

While seeing elite college football players go through these athletic drills makes for great TV, exercise physiologists don’t agree that this set of tests is the best measure of physical ability. Dr. Daniel Robbins, a physiotherapist at the University of Sydney, collected and analyzed the Combine results from the 2005-2009 on all 1,136 players participating and who were eventually drafted to an NFL team. He found that several of the tests are redundant and recommended some adjustments to the process.

The research was published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.

For sprint speed, he found a strong correlation between all three times at 10, 20 and 40 yards, which means if you measure one you can confidently predict the other two times. Scouts and coaches want to understand a player’s acceleration versus their top speed but in that distance there is no way to tease those two metrics apart. Robbins suggested two different tests; a 10 yard dash to measure acceleration from a stationary start and a sprint over 20 yards but with a “flying” start to capture maximum speed.

The two agility tests, 3-cone and shuttle run, were found to be unrelated to the other drills. However, there was a high correlation between each other so one of the tests would be sufficient to measure a player’s ability to change direction. Based on the data, the shuttle run would be the one to keep, as it demonstrates a unique skill.

Next the broad jump matched the results of the sprint and agility drills showing that speed and quickness demonstrated the same lower body strength needed for jumping horizontally. However, the vertical jump results were independent of the other tests, so Robbins recommended keeping it in the Combine. For strength, there is only one test, the bench press, that judges upper body development, used so often in football. So, that test stays.

The final recommendation: break the 40-yard dash into two tests, get rid of the 3-cone test and the broad jump and keep the bench press.

Unfortunately, even if the NFL did change their testing line-up, it still may be a waste of time as a predictor of long-term career success in the league. Back in 2008, two professors at the University of Louisville broke down Combine data for 300 quarterbacks, running backs and wide receivers drafted from 1999-2004. Those “skill” positions were chosen as they have specific game statistics that can be linked to each player.

To measure their pro career success, Frank Kuzmits and Arthur Adams tracked each player’s draft order along with their games played and salaries over their first three seasons. In addition, QB rating, yards per rush and yards per reception were compared for QBs, running backs and wide receivers, respectively.

Their research was also published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.

The only correlation found between workout drill performance at the Combine and NFL success was between the 40-yard dash time for running backs. None of the other test data could predict which player would have a great NFL career. Tracking athlete performance on a daily basis throughout a season would help provide a better record of their physical readiness.

Will this research stop the Combine or the heated discussions among fans about who to draft for their team? Definitely not, but it helps put this event in perspective.