Predicting NFL Success By What Draft Picks Say

/Thankfully, the NFL Draft and all its hype is behind us. The matchmaking is complete but the guessing game begins as to which team picked the right combination of athletic skill, mental toughness and leadership potential in their player selections. Hundreds of hours of game film can be broken down to grade performance with X’s and O’s. Objective athletic tests at the NFL combine rank the NCAA football draftees by speed and strengths, just as the infamous Wonderlic intelligence test tries to rank their brain power.

However, despite all of this data, coaches and general managers often point to a player’s set of fuzzy personal qualities, dubbed the “intangibles”, as the ultimate tie-breaking determinant to future success in the league.

Always looking for the edge in this crystal ball forecasting, teams are turning to other technologies and methods that have been used in related assessment arenas in business and politics. As any good self-improvement speaker will tell you, success leaves clues. By studying established leaders, certain traits, attitudes and themes can be identified as consistent “bread crumbs” left behind for others to follow. In the same way, potential leaders that don’t pan out also demonstrate patterns of behavior that can be linked to their less-than-hyped performance.

Now, a new tool is available to NFL front offices and, as with many high-tech innovations, they have the U.S. military to thank. Achievement Metrics, a risk prediction service for the sports industry, now provides speech content analysis meant to give the odds of a budding superstar either rising into a leadership role or sinking into legal trouble based on just their public comments. Their base technology grew out of the work that their sister company, Social Science Automation, has provided to the CIA and government agencies including profiles of possible terrorists, based on their use of language.

Using only the transcripts from a player’s recent college press conferences or interviews, the company’s computer algorithms find patterns in a player’s words and phrases. Its not just a few vocabulary no-no’s that set off the alarms, but rather a pattern of selected triggers from a “hot list” of over 2000 words. So, unlike the Wonderlic IQ test that might allow for some pre-test cram sessions to increase the score, this analysis is much more intricate and based on an athlete’s words from the past. And, by using just the transcripts of speech, the tone, volume and pronunciation of the words don’t matter; simply the ideas and subconscious selection of phrasing.

Combining numerical text analysis stats such as word meanings and frequency with established psychological profiling theories, players can be categorized in dimensions such as need for power, level of self-centerdness, ability to affect destiny and many more.

Currently, the database includes an analysis of 592 NFL players’ speech patterns matched with their off-field behavior, both positive and negative, with a correlation algorithm. As much as this seems like a scene from Minority Report and the fictional “Pre-Crime” department, the accuracy of the results are impressive, according to the company website:

- 89 percent (89 out of 100) of the players placed in the high-risk category have been arrested or suspended while in the NFL.

- Even more striking, only 0.13 percent (two out of 1,522) of players categorized as low-risk have been arrested or suspended during their professional careers.

- Of the players in the database who have been arrested or suspended while in the NFL, the models placed 98 percent (104 out of 106) in the intermediate- or high-risk category based on their football-related speech from college.

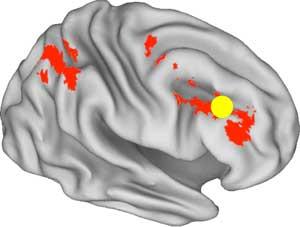

Below is the current scatter plot graph that shows the distribution of NFL subjects along a “bad behavior” continuum from their database. Any college football player who ends up in Areas 3 or 4 after his speech analysis is not good news for his future employer.

Here is Roger Hall, Achievment Metrics’ CEO and psychologist, explaining the process at the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference held in March:

As Hall notes in his presentation, quarterbacks can have a major influence on an NFL team, so there has been much focus on the 2011 crop of draft picks and their chances of success. Not to leave us hanging, Hall recently released the analysis of this group alongside some of the established QBs in the league. On the Y-axis is the Positive Power score, or the level of belief in self-controlled destiny and along the X-axis is Ingroup Affiliation or the level of team orientation. If given a choice, a team would probably prefer their prospect to be in the Aaron Rodgers/ Philip Rivers quadrant rather than the Alex Smith/Matt Leinart quadrant.

Assessing off-field risk is only the beginning for this type of analysis as long as the correlation equals causation relationship is believed and backed up with more data. While some old school scouts and evaluators will cling to their intuitions, more forward-thinking GMs will try any new angle to get the edge. It may just turn out to be a $20 million edge.