Tiger's Brain Is Bigger Than Ours

/

As Tiger Woods heads to Sawgrass for The Players Championship this weekend, mortal golfers wonder what's inside his head that keeps him winning. Well, chances are his brain actually has more gray matter than the average weekend duffer.

Researchers at the University of Zurich have found that expert golfers have a higher volume of the gray-colored, closely packed neuron cell bodies that are known to be involved with muscle control. The good news is that, like Tiger, golfers who start young and commit to years of practice can also grow their brains while their handicaps shrink.

Executing a good golf swing consistently is one of the hardest sport skills to master. Coordinating all of the moving body parts with the right timing requires a brain that has learned from many trial and error repetitions.

In fact, past studies have shown that the number of hours spent practicing is directly related to a golfer's handicap (a calculated number that represents recent playing ability).

Magic number

K. Anders Ericsson, a Florida State professor and the "expert on experts," has spent more than 25 years studying what it takes to become elite in any field, including sports.

The magic number that keeps recurring in Ericsson's studies is 10,000 hours of deliberate practice. If someone is willing to dedicate this amount of structured time on any skill, he has the potential to rise to the top.

Some critics argue that practice is good, but we all start with different levels of innate abilities that put some at an early advantage (i.e. the boy who is six feet tall in fourth grade) While that may be true, Ericsson does not want the rest of us to use that as an excuse. "The traditional assumption is that people come into a professional domain, have similar experiences, and the only thing that's different is their innate abilities," he said in an interview with Fast Company. "There's little evidence to support this. With the exception of some sports, no characteristic of the brain or body constrains an individual from reaching an expert level."

So, what happens to the brain after all of that practice?

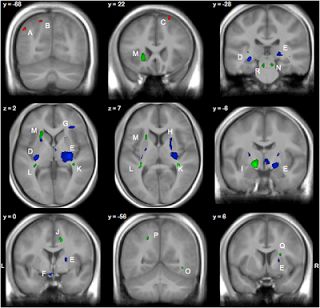

In the new study, a team led by neuropsychologist Lutz Jäncke compared the brain images of 40 men divided into four groups based on their experience as golfers. They recruited ten professional golfers (with handicaps of 0), ten advanced golfers (handicaps between 1 and 14), ten average golfers (handicaps between 15 and 36) and ten volunteers who had never played golf (not even mini-golf!).

Interviews revealed the "practice makes perfect" correlation between hours of practice and lower handicaps.

Brain scans (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) showed that, indeed, there were structural differences, but not in the linear pattern they imagined. While significant differences existed in total volume of gray matter between the pros and the non-players, there was little difference between the pro and the advanced groups or between the average and non-players groups.

When the researchers combined the pros and the advanced golfers into one group called "expert," and the average and non-players into a second group called "novice," a clear dividing line emerged, showing that practice produces a noticeable step up in the brain's gray matter. This jump comes somewhere between 800-3,000 practice hours.

The results were detailed last month in the online journal PLoS ONE.

Step 1: Grow the brain

Another interesting twist is that the pros reported practicing five to eight times more than the advanced group, while the advanced group practiced only twice as much as the average group.

Yet the big jump in gray matter came after golfers achieved a skill level below a 15 handicap, moving from average to advanced. This is consistent with another study in 2008 that measured gray matter volume in students learning to juggle three balls. After learning to juggle for the first time, their gray matter increased. However, once that initial concept was learned, more advanced juggling tricks did not grow more brain cells.

It's been a long time since Tiger's handicap was 15, so clearly the additional years of practice were necessary to reach the top. And, all of that gray has produced a lot of green.

Please visit my other sports science stories at LiveScience.com

Researchers at the University of Zurich have found that expert golfers have a higher volume of the gray-colored, closely packed neuron cell bodies that are known to be involved with muscle control. The good news is that, like Tiger, golfers who start young and commit to years of practice can also grow their brains while their handicaps shrink.

Executing a good golf swing consistently is one of the hardest sport skills to master. Coordinating all of the moving body parts with the right timing requires a brain that has learned from many trial and error repetitions.

In fact, past studies have shown that the number of hours spent practicing is directly related to a golfer's handicap (a calculated number that represents recent playing ability).

Magic number

K. Anders Ericsson, a Florida State professor and the "expert on experts," has spent more than 25 years studying what it takes to become elite in any field, including sports.

The magic number that keeps recurring in Ericsson's studies is 10,000 hours of deliberate practice. If someone is willing to dedicate this amount of structured time on any skill, he has the potential to rise to the top.

Some critics argue that practice is good, but we all start with different levels of innate abilities that put some at an early advantage (i.e. the boy who is six feet tall in fourth grade) While that may be true, Ericsson does not want the rest of us to use that as an excuse. "The traditional assumption is that people come into a professional domain, have similar experiences, and the only thing that's different is their innate abilities," he said in an interview with Fast Company. "There's little evidence to support this. With the exception of some sports, no characteristic of the brain or body constrains an individual from reaching an expert level."

So, what happens to the brain after all of that practice?

In the new study, a team led by neuropsychologist Lutz Jäncke compared the brain images of 40 men divided into four groups based on their experience as golfers. They recruited ten professional golfers (with handicaps of 0), ten advanced golfers (handicaps between 1 and 14), ten average golfers (handicaps between 15 and 36) and ten volunteers who had never played golf (not even mini-golf!).

Interviews revealed the "practice makes perfect" correlation between hours of practice and lower handicaps.

Brain scans (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) showed that, indeed, there were structural differences, but not in the linear pattern they imagined. While significant differences existed in total volume of gray matter between the pros and the non-players, there was little difference between the pro and the advanced groups or between the average and non-players groups.

When the researchers combined the pros and the advanced golfers into one group called "expert," and the average and non-players into a second group called "novice," a clear dividing line emerged, showing that practice produces a noticeable step up in the brain's gray matter. This jump comes somewhere between 800-3,000 practice hours.

The results were detailed last month in the online journal PLoS ONE.

Step 1: Grow the brain

Another interesting twist is that the pros reported practicing five to eight times more than the advanced group, while the advanced group practiced only twice as much as the average group.

Yet the big jump in gray matter came after golfers achieved a skill level below a 15 handicap, moving from average to advanced. This is consistent with another study in 2008 that measured gray matter volume in students learning to juggle three balls. After learning to juggle for the first time, their gray matter increased. However, once that initial concept was learned, more advanced juggling tricks did not grow more brain cells.

It's been a long time since Tiger's handicap was 15, so clearly the additional years of practice were necessary to reach the top. And, all of that gray has produced a lot of green.

Please visit my other sports science stories at LiveScience.com