How To See A 130 MPH Tennis Serve

/

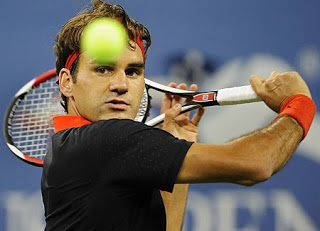

For most of us mere mortals, if an object was coming at us at 120-150 mph, we would be lucky to just get out of the way. Players in this week's U.S. Open tennis tournament not only see the ball coming at them with such speed, but plan where they want to place their return shot and swing their racquet in time to make contact. At 125 mph from 78 feet away, that gives them a little less than a half second to accomplish the task.

How do they do it? Well, they're better than you and I, for one. But science has some more specific answers to offer.

Swiss researchers have concluded that expert tennis players, like their own Roger Federer, have an advantage in certain visual perception skills, while UK scientists have shown how trained animals — and presumably humans — can rely on a superior internal model of motion to predict the path of a fast moving object.

For any sport that involves a moving object, athletes must learn the three levels of response for interceptive timing tasks.

But, in order to reach that cognitive stage, they first need to have excellent optometric and perceptual skills.

Leila Overney and her team at the Brain Mind Institute of Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne (EPFL) studied whether expert tennis players have better visual perception abilities than other athletes and non-tennis players. Typically, motor skill research compares experts to non-experts and tries to deduce what the experts are doing differently to excel.

They carried out seven visual tests, covering a wide range of perceptual functions including motion and temporal processing, object detection and attention, each requiring the participants to push buttons based on their responses to the computer-based tasks and each related to a particular aspect of visual perception.

In this study, which was detailed in the journal PLOS One, Overney wanted to see if the perceptual skills of the tennis players were not only more advanced than non-tennis players but also other athletes of a similar fitness level, (in this case triathletes), to eliminate any benefits of just being in top physical shape. To eliminate the cognitive knowledge difference between the groups, she used seven non-sport specific visual tests which measured different forms of perception including motion and temporal processing, object detection and attention. The participants watched the objects on computer screens and pushed buttons per the specific test instructions.

The tennis players showed significant advantages in the speed discrimination and motion detection tests, while they were no better in the other categories.

"Our results suggest that speed processing and temporal processing is often faster and more accurate in tennis players," Overney writes. They even scored better then their peers, the triathletes. "This is precisely why we added the group of triathletes as controls because they train as hard as tennis players but have lower visual processing demands in their sport."

Still, are the tennis players really just relying on their visual advantage when given that half second to react? Have their years of practice created an internal cognitive model that anticipates and predicts the path of an object?

Nadia Cerminara worked on that question. Cerminara, of the University of Bristol (UK), designed an experiment that taught household cats to reach with their paw at a moving target. If they successfully touched the target, they received a food reward.

After training the cats to be successful, she recorded their neuronal activity in their lateral cerebellum. Then, she measured the activity again but would block the vision of the cats for 200-300 milliseconds while performing the task. Despite the lapse in visual information, the neuron firing activity remained the same as before. Cerminara concluded that an internal model had been used to bridge the gap and provide a prediction of where the object was headed.

The study was published in the Journal of Physiology.

So, when faced with a blistering serve, science suggests that players like Federer not only rely on their superior perceptual skills, but also have created an even faster internal simulation of a ball's flight that can help position them for a winning return.

Of course, you may want to avoid the world's fastest server, Andy Roddick, especially when he's upset from a bad line call (see video). :-)

How do they do it? Well, they're better than you and I, for one. But science has some more specific answers to offer.

Swiss researchers have concluded that expert tennis players, like their own Roger Federer, have an advantage in certain visual perception skills, while UK scientists have shown how trained animals — and presumably humans — can rely on a superior internal model of motion to predict the path of a fast moving object.

For any sport that involves a moving object, athletes must learn the three levels of response for interceptive timing tasks.

- First, there is a basic reaction, also known as optometric reaction (in other words, see it and get out of the way).

- Next, there is a perceptual reaction, meaning you actually can identify the object coming at you and can put it in some context (for example: That is a tennis ball coming at you and not a bird swooping out of the sky).

- Finally, there is a cognitive reaction, meaning you know what is coming at you and you have a plan of what to do with it (return the ball with top-spin down the right line).

But, in order to reach that cognitive stage, they first need to have excellent optometric and perceptual skills.

Leila Overney and her team at the Brain Mind Institute of Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne (EPFL) studied whether expert tennis players have better visual perception abilities than other athletes and non-tennis players. Typically, motor skill research compares experts to non-experts and tries to deduce what the experts are doing differently to excel.

They carried out seven visual tests, covering a wide range of perceptual functions including motion and temporal processing, object detection and attention, each requiring the participants to push buttons based on their responses to the computer-based tasks and each related to a particular aspect of visual perception.

In this study, which was detailed in the journal PLOS One, Overney wanted to see if the perceptual skills of the tennis players were not only more advanced than non-tennis players but also other athletes of a similar fitness level, (in this case triathletes), to eliminate any benefits of just being in top physical shape. To eliminate the cognitive knowledge difference between the groups, she used seven non-sport specific visual tests which measured different forms of perception including motion and temporal processing, object detection and attention. The participants watched the objects on computer screens and pushed buttons per the specific test instructions.

The tennis players showed significant advantages in the speed discrimination and motion detection tests, while they were no better in the other categories.

"Our results suggest that speed processing and temporal processing is often faster and more accurate in tennis players," Overney writes. They even scored better then their peers, the triathletes. "This is precisely why we added the group of triathletes as controls because they train as hard as tennis players but have lower visual processing demands in their sport."

Still, are the tennis players really just relying on their visual advantage when given that half second to react? Have their years of practice created an internal cognitive model that anticipates and predicts the path of an object?

Nadia Cerminara worked on that question. Cerminara, of the University of Bristol (UK), designed an experiment that taught household cats to reach with their paw at a moving target. If they successfully touched the target, they received a food reward.

After training the cats to be successful, she recorded their neuronal activity in their lateral cerebellum. Then, she measured the activity again but would block the vision of the cats for 200-300 milliseconds while performing the task. Despite the lapse in visual information, the neuron firing activity remained the same as before. Cerminara concluded that an internal model had been used to bridge the gap and provide a prediction of where the object was headed.

The study was published in the Journal of Physiology.

So, when faced with a blistering serve, science suggests that players like Federer not only rely on their superior perceptual skills, but also have created an even faster internal simulation of a ball's flight that can help position them for a winning return.

Of course, you may want to avoid the world's fastest server, Andy Roddick, especially when he's upset from a bad line call (see video). :-)