Brains Over Brawn In Sports

/ Sometimes, during my daily browsing of the Web for news and interesting angles on the sport science world, I get lucky and hit a home run. I stumbled on this great May 2007 Wired article by Jennifer Kahn, Wayne Gretzky-Style 'Field Sense' May Be Teachable. It ties together the people and themes of my last three posts, focusing on the concept of perception in sports.

Sometimes, during my daily browsing of the Web for news and interesting angles on the sport science world, I get lucky and hit a home run. I stumbled on this great May 2007 Wired article by Jennifer Kahn, Wayne Gretzky-Style 'Field Sense' May Be Teachable. It ties together the people and themes of my last three posts, focusing on the concept of perception in sports.Wayne Gretzky is often held up as the ultimate example of an athlete with average physical stature, who used his cognitive and perceptual skills to beat opponents. Joining Gretzky in the "brains over brawn" Hall of Fame would be pitcher Greg Maddux, NBA guard Steve Nash and quarterback Joe Montana. They were all told as teenagers that they didn't have the size to succeed in college or the pros, but they countered this by becoming master students of the game, constantly searching for visual cues that would give them the advantage of a fraction of second or the element of surprise.

Kahn's story focuses on two sport scientists that we have met before. Peter Vint, sport technologist with the US Olympic team, who I highlighted in the post, Winning Olympic Gold With Sport Science, comments on this, "In any sport, you come across these players. They're not always the most physically talented, but they're by far the best. The way they see things that nobody else sees — it can seem almost supernatural. But I'm a scientist, so I want to know how the magic works." So, Vint and his team continue to search not only for the secret to the magic, but how it can be taught.

Vint acknowledges the work of one of his fellow sport scientists, Damian Farrow, of the Australian Institute for Sport, who was part of the discussion roundtable mentioned in my post, Getting Sport Science Out Of The Lab And Onto The Field.

He is also fascinated with the perceptual abilities of elite athletes. In his own sport, tennis, he wanted to know how expert players could return serves much better than novice players. Similar to the research we looked at in an earlier post about tennis, Federer and Nadal Can See the Difference, Farrow designed an experiment that would try to identify the cues that players might need to instinctively estimate the speed and direction of a serve. He had three groups of players, expert, non-expert but coached, and non-expert/non-coaced novices, wear ear plugs to block out the sound of the ball hitting the racquet as well as occlusion glasses that could block vision with the touch of an assistant's button.

By changing the point of the serve at which the glasses would go black, and the players would be "blind", he could try to isolate the action of the server that the expert players might be tuned into that the novices were not. The decisive point was immediately before impact between the racquet and the ball. Arm and racquet position at that point seemed to let the expert players estimate the direction of the serve more accurately than the novices.

But Vint and Farrow are not satisfied just knowing what an expert knows. They want to understand how to teach this skill to novices. From his own competitive tennis playing days, Farrow remembers that if he consciously focused his mind on things like arm position, racquet angle, etc., he would be miss the serve as his reaction time would drop. He understood that players need to not only learn the cues, but learn them to the point of "automaticity" through implicit learning.

You may remember our discussion of implicit learning from the post, Teaching Tactics and Techniques in Sports. Malcolm Gladwell, in his best-selling book, Blink, calls this implicit decision-making ability "thin slicing" and gives examples of how we can often make better decisions in the "blink" of an eye, rather than through long analysis. Obviously, in sports, when only seconds or sub-seconds are allowed for decisions, this blink must be so well-trained that it is at the sub-conscious level.

For Vint and Farrow, the experiments continue, looking at each sport, but beyond the raw physical and technical skills that need to be taught but often times are the only skills that are taught.

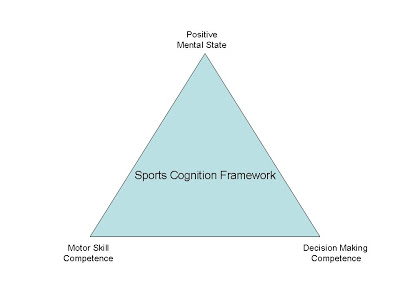

Understanding the cognitive side of the game will provide the edge when all else is equal.