Lifting The Fog Of Sports Concussions

/

A concussion, clinically known as a Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (MTBI), is one of the most common yet least understood sports injuries. According to the Centers for Disease Control, there are as many as 300,000 sports and recreation-related concussions each year in the U.S., yet the diagnosis, immediate treatment and long-term effects are still a mystery to most coaches, parents and even some clinicians.

A concussion, clinically known as a Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (MTBI), is one of the most common yet least understood sports injuries. According to the Centers for Disease Control, there are as many as 300,000 sports and recreation-related concussions each year in the U.S., yet the diagnosis, immediate treatment and long-term effects are still a mystery to most coaches, parents and even some clinicians. The injury can be deceiving as there is rarely any obvious signs of trauma. If the head is not bleeding and the player either does not lose consciouness or regains it after a brief lapse, the potential damage is hidden and the usual "tough guy" mentality is to "shake it off" and get back in the game.

Leigh Steinberg, agent and representative to some of the top professional athletes in the world (including NFL QBs Ben Roethlisberger and Matt Leinart), is tired of this ignorance and attitude. "My clients, from the day they played Pop Warner football, are taught to believe ignoring pain, playing with pain and being part of the playing unit was the most important value," Steinberg said, "I was terrified at the understanding of how tender and narrow that bond was between cognition and consciousness and dementia and confusion". Which is why he was the keynote speaker at last week's "New Developments in Sports-Related Concussions" conference hosted by the University of Pittsburgh Medical College Sport Medicine Department in Pittsburgh.

Leading researchers gathered to discuss the latest research on sports-related concussions, their diagnosis and treatment. "There's been huge advancement in this area," said Dr. Micky Collins, the assistant director for the UPMC Sports Medicine Program. "We've learned more in the past five years than the previous 50 combined."

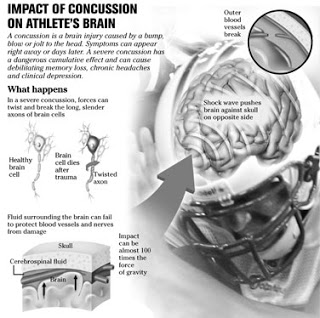

So, what is a concussion? The CDC defines a concussion as "a complex pathophysiologic process affecting the brain, induced by traumatic biomechanical forces secondary to direct or indirect forces to the head." Being a "mild" form of traumatic brain injury, it is generally believed that there is no actual structural damage to the brain from a concussion, but more a disruption in the biochemistry and electrical processes between neurons.

The brain is surrounded by cerebrospinal fluid, which is supposed to provide some protection from minor blows to the head. However, a harder hit can cause rotational forces that affect a wide area of the brain, but most importantly the mid-brain and the reticular activating system which may explain the loss of consciousness in some cases.

For some athletes, the concussion symptoms take longer to disappear in what is known as post-concussion syndrome. It is not known whether this is from some hidden structural damage or more permanent disruption to neuronal activity. Repeated concussions over time can lead to a condition known as dementia pugilistica, with long-term impairments to speech, memory and mental processing.

After the initial concussion, returning to the field before symptoms clear raises the risk of second impact syndrome, which can cause more serious, long-term effects. As part of their "Heads Up" concussion awareness campaign, the CDC offers this video story of Brandon Schultz, a high school football player, who was not properly diagnosed after an initial concussion and suffered a second hit the following week, which permanently changed his life. Without some clinical help, the player, parents and coach can only rely on the lack of obvious symptoms before declaring a concussion "healed".

However, making this "return to play" decision is now getting some help from some new post-concussion tests. The first is a neurological skills test called ImPACT (Immediate Post-Concussion and Cognitive Testing) created by the same researchers at UPMC. It is an online test given to athletes after a concussion to measure their performance in attention span, working memory, sustained and selective attention time, response variability, problem solving and reaction time. Comparing a "concussed" athlete's performance on the test with a baseline measurement will help the physician decide if the brain has healed sufficiently.

However, Dr. Collins and his team wanted to add physiological data to the psychological testing to see if there was a match between brain activity, skill testing and reported symptoms after a concussion. In a study released last year in the journal Neurosugery, they performed functional MRI (fMRI) brain imaging studies on 28 concussed high-school athletes while they performed certain working memory tasks to see if there was a significant link between performance on the tests and changes in brain activation. They were tested about one week after injury and again after the normal clinical recovery period.

“In our study, using fMRI, we demonstrate that the functioning of a network of brain regions is significantly associated with both the severity of concussion symptoms and time to recover,” said Jamie Pardini, Ph.D., a neuropsychologist on the clinical and research staff of the UPMC concussion program and co-author of the study.

"We identified networks of brain regions where changes in functional activation were associated with performance on computerized neurocognitive testing and certain post-concussion symptoms,” Dr. Pardini added. "Also, our study confirms previous research suggesting that there are neurophysiological abnormalities that can be measured even after a seemingly mild concussion.”

Putting better assessment tools in the hands of athletic trainers and coaches will provide evidence-based coaching decisions that are best for the athlete's health. Better decisions will also ease the minds of parents knowing their child has fully recovered from their "invisible" injury.

Lovell, M.R., Pardini, J.E., Welling, J., Collins, M.W., Bakal, J., Lazar, N., Roush, R., Eddy, W.F., Becker, J.T. (2007). FUNCTIONAL BRAIN ABNORMALITIES ARE RELATED TO CLINICAL RECOVERY AND TIME TO RETURN-TO-PLAY IN ATHLETES. Neurosurgery, 61(2), 352-360. DOI: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000279985.94168.7F