Baseball Brains - Hitting Into The World Series

/ Ted Williams, arguably the greatest baseball hitter of all-time, once said, "I think without question the hardest single thing to do in sport is to hit a baseball". Williams was the last major league player to hit .400 for an entire season and that was back in 1941, 67 years ago! In the 2008 Major League Baseball season that just ended, the league batting average for all players was .264, while the strikeout percentage was just under 20%. So, in ten average at-bats, a professional ballplayer, paid millions of dollars per year, gets a hit less than 3 times but fails to even put the ball in play 2 times. So, why is hitting a baseball so difficult? What visual, cognitive and motor skills do we need to make contact with an object moving at 70-100 mph?

Ted Williams, arguably the greatest baseball hitter of all-time, once said, "I think without question the hardest single thing to do in sport is to hit a baseball". Williams was the last major league player to hit .400 for an entire season and that was back in 1941, 67 years ago! In the 2008 Major League Baseball season that just ended, the league batting average for all players was .264, while the strikeout percentage was just under 20%. So, in ten average at-bats, a professional ballplayer, paid millions of dollars per year, gets a hit less than 3 times but fails to even put the ball in play 2 times. So, why is hitting a baseball so difficult? What visual, cognitive and motor skills do we need to make contact with an object moving at 70-100 mph? In the second of three posts in the Baseball Brains series, we'll take a quick look at some of the theory behind this complicated skill. Once again, we turn to Professor Mike Stadler and his book "The Psychology of Baseball" for the answers. First, here's the "Splendid Splinter" in action:

A key concept of pitching and hitting in baseball was summed up long ago by Hall of Fame pitcher Warren Spahn, when he said, “Hitting is timing. Pitching is upsetting timing.” To sync up the swing of the bat with the exact time and location of the ball's arrival is the challenge that each hitter faces. If the intersection is off by even tenths of a second, the ball will be missed. Just as pitchers need to manage their targeting, the hitter must master the same two dimensions, horizontal and vertical. The aim of the pitch will affect the horizontal dimension while the speed of the pitch will affect the vertical dimension. The hitter's job is to time the arrival of the pitch based on the estimated speed of the ball while determining where, horizontally, it will cross the plate. The shape of the bat helps the batter in the horizontal space as its length compensates for more error, right to left. However, the narrow 3-4" barrel does not cover alot of vertical ground, forcing the hitter to be more accurate judging the vertical height of a pitch than the horizontal location. So, if a pitcher can vary the speed of his pitches, the hitter will have a harder time judging the vertical distance that the ball will drop as it arrives, and swing either over the top or under the ball.

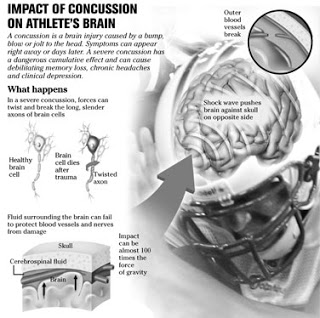

A common coach's tip to hitters is to "keep your eye on the ball" or "watch the ball hit the bat". As Stadler points out, doing both of these things is nearly impossible due to the concept known as "angular velocity". Imagine you are standing on the side of freeway with cars coming towards you. Off in the distance, you are able to watch the cars approaching your position with relative ease, as they seem to be moving at a slower speed. As the cars come closer and pass about a 45 degree angle and then zoom past your position, they seem to "speed up" and you have to turn your eyes/head quickly to watch them. While the car is going at a constant speed, its angular velocity increases making it difficult to track.

This same concept applies to the hitter. As the graphic above shows (click to enlarge), the first few feet that a baseball travels when it leaves a pitcher's hand is the most important to the hitter, as the ball can be tracked by the hitter's eyes. As the ball approaches past a 45 degree angle, it is more difficult to "keep your eye on the ball" as your eyes need to shift through many more degrees of movement. Research reported by Stadler shows that hitters cannot watch the entire flight of the ball, so they employ two tactics.

First, they might follow the path of the ball for 70-80% of its flight, but then their eyes can't keep up and they estimate or extrapolate the remaining path and make a guess as to where they need to swing to have the bat meet the ball. In this case, they don't actually "see" the bat hit the ball. Second, they might follow the initial flight of the ball, estimate its path, then shift their eyes to the anticipated point where the ball crosses the plate to, hopefully, see their bat hit the ball. This inability to see the entire flight of the ball to contact point is what gives the pitcher the opportunity to fool the batter with the speed of the pitch. If a hitter is thinking "fast ball", their brain will be biased towards completing the estimated path across the plate at a higher elevation and they will aim their swing there. If the pitcher actually throws a curve or change-up, the speed will be slower and the path of the ball will result in a lower elevation when it crosses the plate, thus fooling the hitter.

To demonstrate the effect of reaction time for the batter, FSN Sport Science compared hitting a 95 mph baseball at 60' 6" versus a 70 mph softball pitched from 43' away. The reaction time for the hitter went from .395 seconds to .350 seconds, making it actually harder to hit. That's not all that makes it difficult. Take a look:

As in pitching, the eyes and brain determine much of the success for hitters. The same concepts apply to hitting any moving object in sports; tennis, hockey, soccer, etc. Over time, repeated practice may be the only way to achieve the type of reaction speed that is necessary, but even for athletes who have spent their whole lives swinging a bat, there seems to be human limitation to success. Tracking a moving object through space also applies to catching a ball, which we'll look at next time.