Exercise Pumps Up Your Brain

/

Regular exercise speeds learning and improves blood flow to the brain, according to a new study led by researchers from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine that is the first to examine these relationships in a non-human primate model. The findings are available in the journal Neuroscience.

While there is ample evidence of the beneficial effects of exercise on cognition in other animal models, such as the rat, it has been unclear whether the same holds true for people, said senior author Judy L. Cameron, Ph.D., a psychiatry professor at Pitt School of Medicine and a senior scientist at the Oregon National Primate Research Center at Oregon Health and Science University. Testing the hypothesis in monkeys can provide information that is more comparable to human physiology.

"We found that monkeys who exercised regularly at an intensity that would improve fitness in middle-aged people learned to do tests of cognitive function faster and had greater blood volume in the brain's motor cortex than their sedentary counterparts," Dr. Cameron said. "This suggests people who exercise are getting similar benefits."

For the study, the researchers trained adult female cynomolgus monkeys to run on a human-sized treadmill at 80 percent of their individual maximal aerobic capacity for one hour each day, five days per week, for five months. Another group of monkeys remained sedentary, meaning they sat on the immobile treadmill, for a comparable time. Half of the runners went through a three-month sedentary period after the exercise period. In all groups, half of the monkeys were middle aged (10 to 12 years old) and the others were more mature (15 to 17 years old). Initially, the middle-aged monkeys were in better shape than their older counterparts, but with exercise, all the runners became more fit.

During the fifth week of exercise training, standardized cognitive testing was initiated and then performed five days per week until week 24. In a preliminary task, the monkeys learned that by lifting a cover off a small well in the testing tray, they could have the food reward that lay within it. In a spatial delay task, a researcher placed a food reward in one of two wells and covered both wells in full view of the monkey. A screen was lowered to block the animal's view for a second, and then raised again. If the monkey displaced the correct cover, she got the treat. After reliably succeeding at this task, monkeys that correctly moved the designated one of two different objects placed over side-by-side wells got the food reward that lay within it.

During the fifth week of exercise training, standardized cognitive testing was initiated and then performed five days per week until week 24. In a preliminary task, the monkeys learned that by lifting a cover off a small well in the testing tray, they could have the food reward that lay within it. In a spatial delay task, a researcher placed a food reward in one of two wells and covered both wells in full view of the monkey. A screen was lowered to block the animal's view for a second, and then raised again. If the monkey displaced the correct cover, she got the treat. After reliably succeeding at this task, monkeys that correctly moved the designated one of two different objects placed over side-by-side wells got the food reward that lay within it.

"Monkeys that exercised learned to remove the well covers twice as quickly as control animals," Dr. Cameron said. "Also, they were more engaged in the tasks and made more attempts to get the rewards, but they also made more mistakes."

She noted that later in the testing period, learning rate and performance was similar among the groups, which could mean that practice at the task will eventually overshadow the impact of exercise on cognitive function.

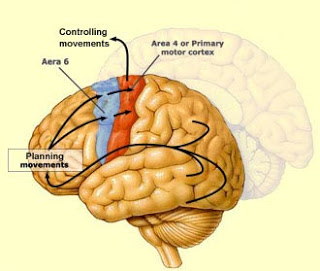

When the researchers examined tissue samples from the brain's motor cortex, they found that mature monkeys that ran had greater vascular volume than middle-aged runners or sedentary animals. But those blood flow changes reversed in monkeys that were sedentary after exercising for five months.

"These findings indicate that aerobic exercise at the recommended levels can have meaningful, beneficial effects on the brain," Dr. Cameron said. "It supports the notion that working out is good for people in many, many ways."

Source: University of Pittsburgh Schools of the Health Sciences.

See also: Take Your Brain To The Gym and Boomer Brains Need Exercise

While there is ample evidence of the beneficial effects of exercise on cognition in other animal models, such as the rat, it has been unclear whether the same holds true for people, said senior author Judy L. Cameron, Ph.D., a psychiatry professor at Pitt School of Medicine and a senior scientist at the Oregon National Primate Research Center at Oregon Health and Science University. Testing the hypothesis in monkeys can provide information that is more comparable to human physiology.

"We found that monkeys who exercised regularly at an intensity that would improve fitness in middle-aged people learned to do tests of cognitive function faster and had greater blood volume in the brain's motor cortex than their sedentary counterparts," Dr. Cameron said. "This suggests people who exercise are getting similar benefits."

For the study, the researchers trained adult female cynomolgus monkeys to run on a human-sized treadmill at 80 percent of their individual maximal aerobic capacity for one hour each day, five days per week, for five months. Another group of monkeys remained sedentary, meaning they sat on the immobile treadmill, for a comparable time. Half of the runners went through a three-month sedentary period after the exercise period. In all groups, half of the monkeys were middle aged (10 to 12 years old) and the others were more mature (15 to 17 years old). Initially, the middle-aged monkeys were in better shape than their older counterparts, but with exercise, all the runners became more fit.

During the fifth week of exercise training, standardized cognitive testing was initiated and then performed five days per week until week 24. In a preliminary task, the monkeys learned that by lifting a cover off a small well in the testing tray, they could have the food reward that lay within it. In a spatial delay task, a researcher placed a food reward in one of two wells and covered both wells in full view of the monkey. A screen was lowered to block the animal's view for a second, and then raised again. If the monkey displaced the correct cover, she got the treat. After reliably succeeding at this task, monkeys that correctly moved the designated one of two different objects placed over side-by-side wells got the food reward that lay within it.

During the fifth week of exercise training, standardized cognitive testing was initiated and then performed five days per week until week 24. In a preliminary task, the monkeys learned that by lifting a cover off a small well in the testing tray, they could have the food reward that lay within it. In a spatial delay task, a researcher placed a food reward in one of two wells and covered both wells in full view of the monkey. A screen was lowered to block the animal's view for a second, and then raised again. If the monkey displaced the correct cover, she got the treat. After reliably succeeding at this task, monkeys that correctly moved the designated one of two different objects placed over side-by-side wells got the food reward that lay within it."Monkeys that exercised learned to remove the well covers twice as quickly as control animals," Dr. Cameron said. "Also, they were more engaged in the tasks and made more attempts to get the rewards, but they also made more mistakes."

She noted that later in the testing period, learning rate and performance was similar among the groups, which could mean that practice at the task will eventually overshadow the impact of exercise on cognitive function.

When the researchers examined tissue samples from the brain's motor cortex, they found that mature monkeys that ran had greater vascular volume than middle-aged runners or sedentary animals. But those blood flow changes reversed in monkeys that were sedentary after exercising for five months.

"These findings indicate that aerobic exercise at the recommended levels can have meaningful, beneficial effects on the brain," Dr. Cameron said. "It supports the notion that working out is good for people in many, many ways."

Source: University of Pittsburgh Schools of the Health Sciences.

See also: Take Your Brain To The Gym and Boomer Brains Need Exercise